As Donald Trump and JD Vance barnstorm the country, laying out their vision of a Gileadean America, one word — repeated by media on the left, right and center — follows them everywhere.

The New York Times: Vance Honed Populist Views in the Senate, Auditioning for Trump

PBS: Trump urges unity after assassination attempt, proposes sweeping populist agenda in 2024 RNC finale

AP News: JD Vance charted a Trump-centric, populist path in Senate as he fought GOP establishment

Fox News: Trump VP pick JD Vance pledges to ‘commit to the working man’ as populism takes center stage at RNC

USA Today: Trump's takeover: In a redefined GOP, populism and a new coalition. Goodbye, old guard

Al Jazeera: JD Vance hails Trump, outlines populist vision as he accepts VP spot at RNC

Mother Jones: JD Vance’s Racist Populism

The Economist: Donald Trump’s populism is turning off corporate donors

Fortune: JD Vance, venture capitalist turned populist Ohio senator, will be Trump’s VP pick

Wall Street Journal: Mitch McConnell Couldn’t Fend Off Trump’s Populist Takeover

Over the last eight years, populist become practically synonymous with Trump. Why?

Let’s clarify up front that populist is not synonymous with popular.

From Merriam-Webster:

Populist: a member of a political party claiming to represent the common people

Popular: of or relating to the general public

The Oxford English Dictionary’s first three populist definitions are history-specific — referring to particular moments in American, Russian and French history, respectively — but the fourth gets broader:

Populist: A person who seeks to represent or appeal to the interests of ordinary people.

Even if popular and populist aren’t synonyms, they’re loaded terms. Both Merriam-Webster’s and the OED’s definitions suggest a salt-of-the-earth motivation that, let’s be honest, doesn’t exactly reflect the mores of the modern Republican Party.

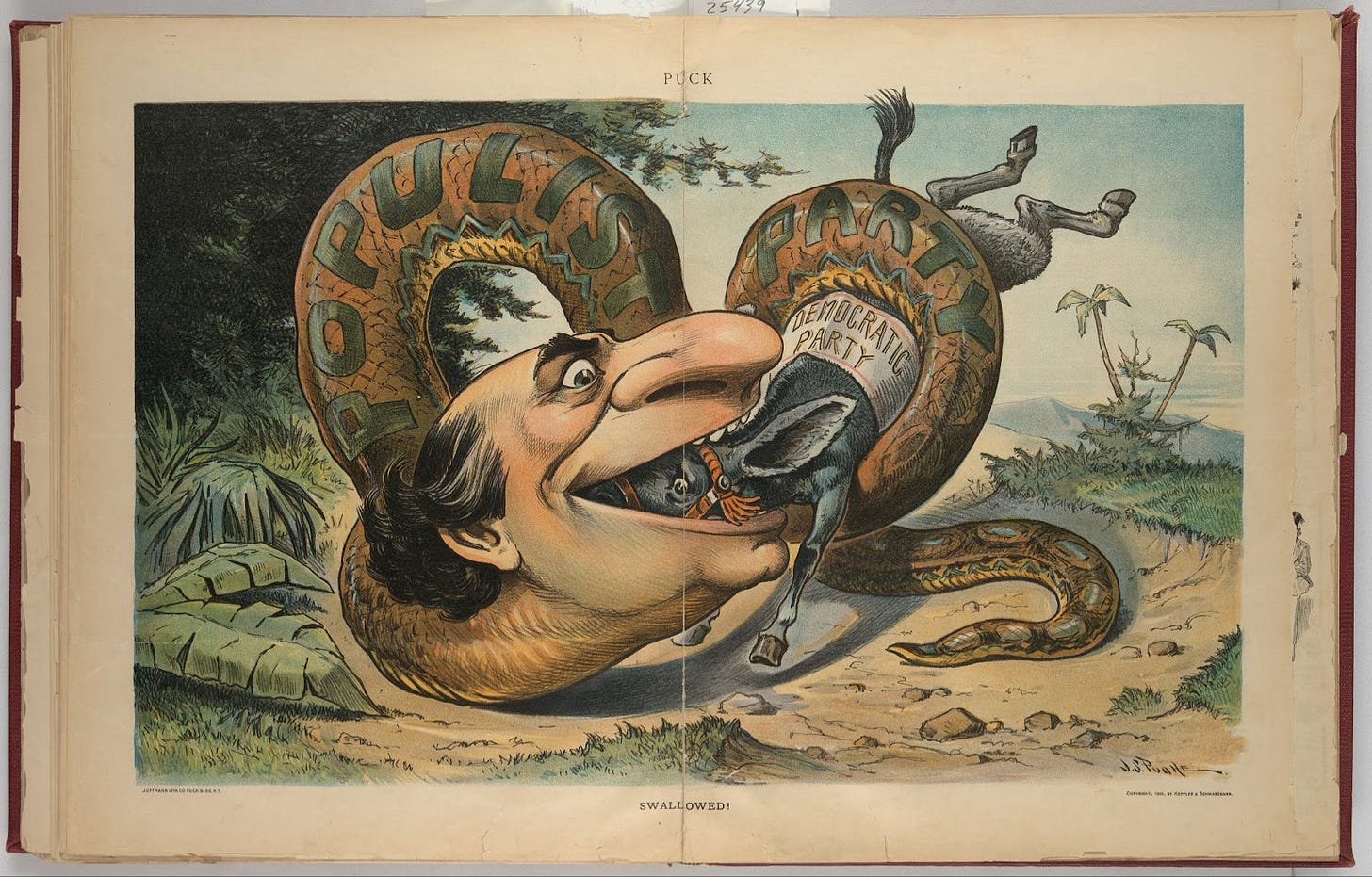

Throughout history, populist has often carried positive connotations for anyone who wasn’t the elite. When it first surfaced in the U.S. in the late 19th century, it was the effective branding of a new political party. Well, kind of effective, anyway: After a respectable showing in the 1892 election (8.5% of the popular vote and 5% of the Electoral College — numbers that RFK Jr. would kill a bear for), the People’s Party fizzled. But in its wake, populism lived on as a word and concept, arriving at its current, more general definition by the mid-20th century.

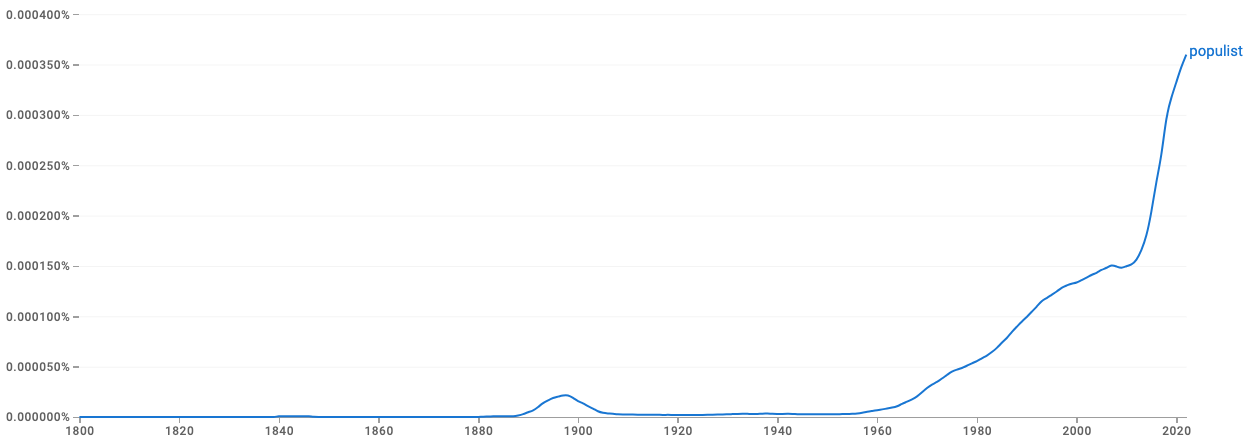

The following chart shows the usage of populist in books. While there’s a slight blip when the political party was actually active, usage picked up only in the last 40 years — and especially in the last 10.

The NOW Corpus tracks words used in web-based newspapers and magazines from 2010 to the present. Check out what happened to the prevalence of the word populist in 2016, a year that saw both Brexit and the rise of Donald Trump:

Usage has remained high through the present.

Even if populism and populist began in a specific historical context, they shed that context long ago. Particularly when words’ meanings change, their ambiguity can lead to misperceptions about what the word actually means. When people are unsure of a definition, they make assumptions.

Given that populist sounds so much like popular — and they share an etymology — a casual reader might mistake Trump and Vance’s populist policies for ones that are actually popular. Which they’re not.

My friend Catherine Rampell at the Washington Post regularly publishes excellent analyses of just how unpopular the Republican policy platform actually is. On issues from immigration to taxes to the economy, Republican policies are consistently less popular than the Republican politicians who propose them are.

Calling Republican policies populist doesn’t mean that they’re popular. But it means that readers might perceive them as popular.

The populist label is lazy, and usually misapplied. We need a new word — if only to help voters understand what exactly they’re signing up for.

Americans got it in 1892; will they in 2024?

Recording is underway for the soundtrack to The Angry Grammarian, and tickets for next month’s run of the musical (Sept. 20-29 at the Arden Theatre in Philadelphia) are selling quickly. Get them here — nine shows only!